Reproducibility and Workflow Management

What is Reproducibility?¶

Reproducibility (closely related to replicability and repeatability) is a major principle underpinning the scientific method. For the findings of a study to be reproducible means that results obtained by an experiment or an observational study or in a statistical analysis of a data set should be achieved again with a high degree of reliability when the work is done again. There are different kinds of “re-doing” depending on whether the data, methods and team involved in the analysis are the same.

What are the differences between the terms?

Definitions¶

🔄 Repeatability¶

Definition: The ability to obtain the same results using the same experimental or observational setup, under the same conditions by the same team (that I think is optional).

Key Ideas:

It assesses short-term consistency or measurement precision.

Often applies to hardware, instruments, or observational setups.

It’s about within-lab or within-operator consistency.

Focus: Measurement precision or consistency between different experiments.

Who: Same or different researcher or team

Example: Observing a number of different transit events and getting consistent results between the analsys of each transit.

🔁 Reproducibility¶

Definition: The ability to obtain the same results using the same data and the same code or analysis pipeline, but by the same or a different team or at a later time (by the same team).

Key Ideas:

Someone else (or you, later) runs the original code on the original data and gets the same outputs.

It tests whether the results can be regenerated given full access to the computational environment and materials.

Focus: Computational consistency

Who: Same team

Example: Running the original author’s code on the same dataset and getting the same figures or numbers.

🧪 Replicability¶

Definition: The ability to obtain consistent results using new data or a different setup that tests the same hypothesis.

Key Ideas:

A different study, possibly with different tools or in a different setting, confirms the findings.

It’s a stronger test of the scientific claim than reproducibility.

Focus: Scientific validity and generalizability

Who: Different team, new data or methods

Example: A separate survey confirming the same cosmological parameter trends using different observations and analysis techniques. Only after one or several such successful replications should a result be recognized as scientific knowledge.

Examples¶

Example 1: Galaxy Stellar Mass Function¶

Repeatability:

The same team runs their mass function estimation pipeline multiple times on SDSS data and gets consistent results each time.Reproducibility:

Another researcher downloads the original team’s SDSS data and code, runs the pipeline, and recovers the same mass function plots and numbers.Replicability:

A different group uses COSMOS survey data and a different method for mass estimation, but finds a similar shape and evolution of the mass function.

Example 2: Exoplanet Detection via Transit Method¶

Repeatability:

The original team processes the same Kepler light curve for a star multiple times and consistently detects the same transit signal.Reproducibility:

Another researcher uses the same Kepler data and published code, re-runs the analysis, and recovers the same orbital parameters of the planet.Replicability:

An independent team uses TESS or a ground-based telescope to observe the same star and detects the same exoplanet with similar properties, using a different pipeline.

Example 3: Weak Lensing in Cluster Surveys¶

Repeatability:

The original team measures shear profiles from DES images of clusters multiple times and consistently obtains the same lensing signals.Reproducibility:

Another team uses the same DES data and shape measurement code, and reproduces the same cluster mass estimates.Replicability:

A different group uses HSC or KiDS data and a different shape measurement method, and independently finds consistent weak lensing signals for similar cluster populations.

What if we use the same data but a different method?

When you use the same data but a different method (e.g. reanalyze spectra with a different fitting model, or estimate redshifts with a new algorithm), you’re testing whether the result holds up across methodological choices.

This is typically classified under reproducibility, especially in computational sciences, but some fields also refer to this more narrowly as methodological reproducibility or analytic robustness.

Why is reproducibility important?¶

Reproducibility is crucial in research because it is the foundation of scientific integrity, trust, and progress. Here are the key reasons why:

🧭 1. Verifies Scientific Accuracy: If a result can be independently reproduced using the same data and code, it confirms that the original analysis was correctly performed. It helps catch mistakes, bugs, or unintentional biases in data processing.

🔍 2. Builds Trust and Transparency: Open, reproducible research allows others to see exactly how results were obtained.This transparency increases confidence in the findings, especially in high-impact or policy-relevant work.

🔁 3. Enables Reuse and Extension: Other researchers can build on your work more easily if your code and data are available and reproducible. This accelerates discovery and innovation by reducing duplication of effort.

🧪 4. Supports Scientific Self-Correction: Science advances by challenging and refining previous findings. Reproducibility allows the community to evaluate which results are robust and which need revision.

📈 5. Enhances Training and Education: Well-documented, reproducible research makes it easier to teach students and early-career researchers how complex analyses are done in practice.

💼 6. Improves Credibility with Funders and Journals: Many funders, journals, and institutions now require data and code sharing as part of reproducibility and open science initiatives.

In short, reproducibility turns research from a personal insight into a public contribution — one that others can understand, verify, and build on.

BUT IT’S. SO. HARD.¶

Yes, it is hard to make work reproducible after the fact. Not so much if you start working with reproducibility in mind.

Try out the tools we cover today as part of your next project, not for your coleagues, but for yourself, and see if you find any use in them.

Reproductions Packages¶

One way to make sure you have a good organization of your project is to use a template for organization. A template that helps you organize your data and scripts for a paper that helps a student reproduce your work. Depending on the project this may include:

- Links to raw data

- Scripts that derive products (reduction)

- The reduced/derivative products

- Analysis scrips

- Results tables

- Scripts to create each figure

- README that describes it all:

- software requirements

- data prerequisites

Example Structure:

- data/

- figures/

- notebooks/

- README.md

Existing Templates¶

The “easiest” way to create a reproducible workflow is to use a template that forces you to capture all the necessary information in the same place.

Open data template: https://

Data Science Cookiecutter: https://

Show your work: https://

(Notice all the .gitignores!!! The data should not go in the repo!!!)

Work through the Installation and quickstart pages.

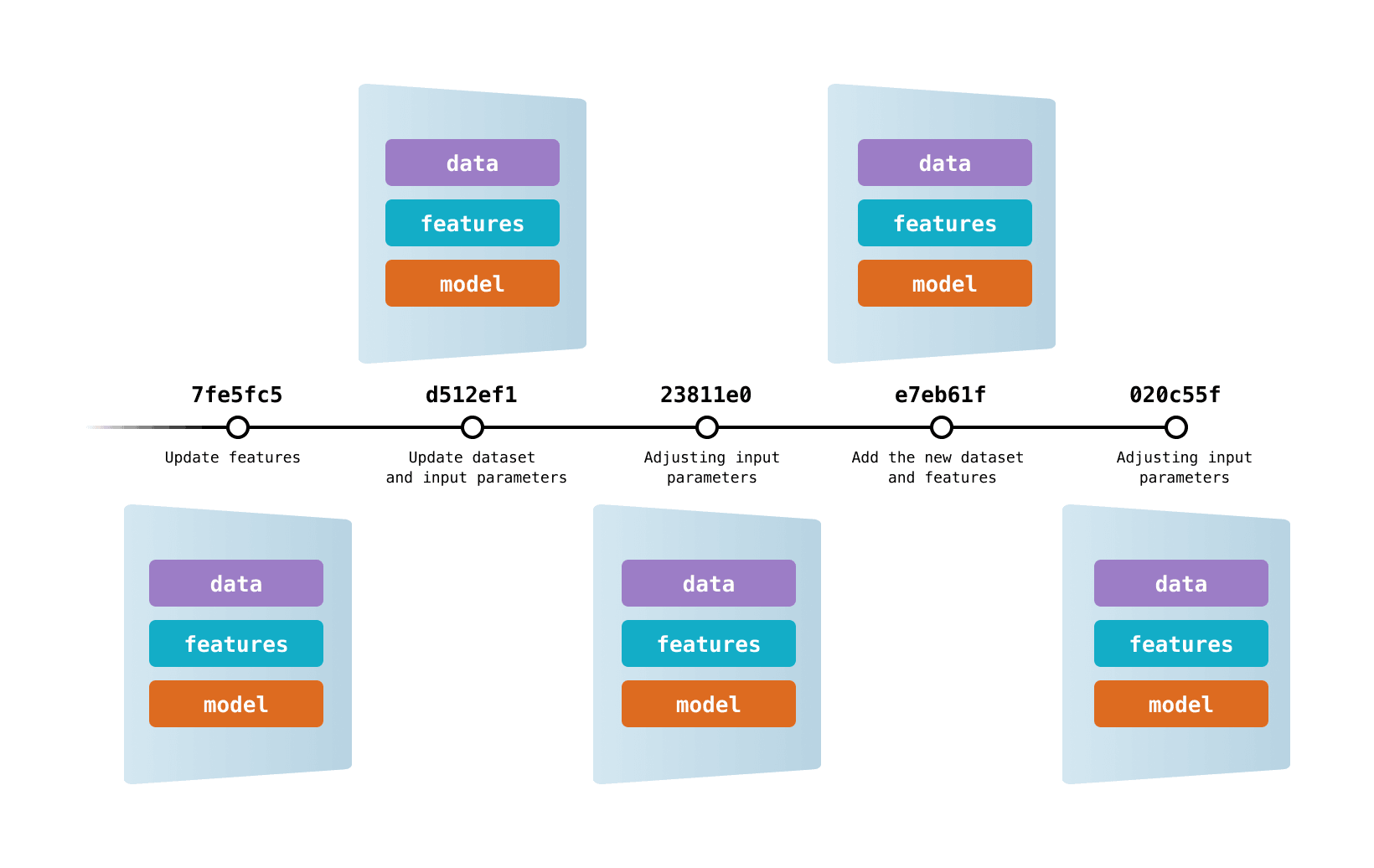

Data Versioning¶

🔹 1. Manual Versioning (File-Based) Store datasets as separate files with explicit version labels (e.g. data_v1.csv, data_v2.1.fits).

Simple but error-prone for large or collaborative projects.

Pros: Easy to implement Cons: No change tracking or metadata; manual bookkeeping

🔹 2. Checksum or Hashing Use tools like md5sum or sha256 to generate a fingerprint of a dataset.

Include the hash in your publication or README to verify exact versions.

Pros: Verifies data integrity Cons: Doesn’t help manage versions—just verifies them

🔹 3. Git or Git-LFS (for Small/Medium Files) Git can track small text-based datasets.

Git-LFS (Large File Storage) supports larger files (like .csv, .fits, or .hdf5) by storing them outside the Git repository while keeping version history.

Pros: Version control with history; integrates with Git workflows Cons: Git doesn’t scale well to very large datasets or binary blobs

🔹 4. DVC (Data Version Control) A Git-like tool specifically for tracking datasets and models.

Stores metadata in Git and data itself in remote storage (e.g., S3, GDrive, Azure Blob).

Pros: Designed for machine learning and scientific workflows; integrates well with code Cons: Adds some setup complexity; collaborators need to install DVC

🔹 5. Zenodo, Figshare, or Dryad (DOI-Based Archives) Upload a dataset to a long-term repository that provides a DOI (Digital Object Identifier).

Some platforms (like Zenodo) allow versioned deposits with persistent links.

Pros: Citable, FAIR-compliant, supports open access Cons: Not designed for frequent updates or large datasets (> GBs–TBs)

🔹 6. Dataverse or Institutional Repositories Supports formal data publication with versioning, metadata, and access control.

Good for institutional reproducibility mandates.

Pros: Robust metadata; structured versioning; long-term preservation Cons: Varies by institution; may be less flexible for large-scale collaborative workflows

🔹 7. Database Snapshots If working with dynamic databases (e.g., SQL, APIs), take a snapshot (dump) and record the timestamp or version.

Save as a static file or container image for reproducibility.

Pros: Captures dynamic sources Cons: Snapshots can be large and hard to archive if not properly compressed/indexed

| Task | Recommended Tool/Platform |

|---|---|

| Simple file tracking | Git + semantic filenames |

| Binary or large files | Git-LFS, DVC |

| Long-term, citable archive | Zenodo, Figshare, Dryad |

| Team-scale reproducibility | DVC + remote storage |

| Dynamic or database-based data | Snapshots with version tags |

Data Versioning by Volume:¶

| Data Volume | Recommended Tools / Strategies |

|---|---|

| < 1 GB | - Git (for text/CSV) - Git-LFS (for binary files) - Zenodo/Figshare for archiving |

| 1–10 GB | - Git-LFS (for moderate file sizes) - DVC with remote storage (e.g., S3, GDrive) - Archive to Zenodo with DOIs |

| 10–100 GB | - DVC with S3, Azure, or institutional object storage - RClone or rsync for syncing large datasets - Publish a snapshot to Zenodo (check size limits) or institutional repository |

| 100 GB–1 TB | - DVC or Pachyderm for full data pipelines - Use structured cloud storage buckets - Archive metadata and reference paths (not full data) in Git Institutional repositories |

| 1–10 TB | - DVC + scalable cloud storage (e.g., AWS S3, Google Cloud Storage) - Snapshot-based backups (e.g., ZFS/Btrfs or database dumps) - Version using hash-based manifest files or tools like Quilt - DOIs should reference access instructions, not raw files Institutional repositories |

Zenodo limits (https://

Default Limit: 50GB total file size per record, with a maximum of 100 files. Quota Increase: One-time quota increases of up to 200GB are available for a single record. File Limit: While the default is 100 files, larger files can be accommodated by archiving them into a ZIP file, according to Zenodo. Case-by-case basis: Zenodo may also grant quota increases on a case-by-case basis if you need more space, says OpenAIRE.

Git-LFS also has limits:

Product Maximum file size GitHub Free 2 GB GitHub Pro 2 GB GitHub Team 4 GB GitHub Enterprise Cloud 5 GB

DVC¶

What is it and how it works: https://

Options for remote storage:

https://

Installation: https://

Versioning and data models tutorial:

https://

Versioning and data models tutorial:

https://

Workflows¶

Make:

https://

Snakemake¶

https://

Pixi and Snakemake¶

PyCon talk by Raphael:

https://

Pixi:

https://

Containers¶

https://

https://

One step further: Open Workflows¶

(Based on Goodman et al., 2014, Ten Simple Rules for the Care and Feeding of Scientific Data)

Data Science Experiment Trackers¶

Weights and biases: https://

AimStack: https://

What is reasonable reuse?¶

It is practically impossible to document every singe decision that goes into making a dataset. Some choices will seem arbitrary, some will have to be arbitraty, most will not be the bestest choices for the people who want to reuse your data. So think of what level of reproducibiluty you want your users to have? What is a reasonable level of reproducibility your users may hope for or expect?

- If you want/need all your work to be fully reproducible, then every steps needs to be documented in code, including environemt, raw data, etc.

- Maybe your work just needs to be inspectable. Maybe code is enough.

- Or maybe just your data needs to be usable. Maybe just data in standard formats + docs is enough.

Publish Workflow¶

There are applicatins that are dedicated to managing sequences of reduction and analysis steps (Taverna, Kepler, Wings, etc.). These are not used in astro.

Instead consider publishing your Jupyter notebooks. I think AAS will publish notebooks.

Publish your snakemake files.

And your SLURM scripts.

Publish your code.¶

Put your code on github, add a licence, archive on Zenodo, add DOI to GitHub. And add a CITATION.cff file. Just do it. Better published than tidy.

Attend the workshop on software packaging.

Also JOSS (for significant scholarly effort). Joint publications with AAS.

Link your workflows and your data in your papers.¶

Papers are still the most findable artifacts in research.

Always state how you want to get credit!¶

How should people cite your code? How should they cite your data? Don’t make them cite an (in prep.) paper. Use DOIs and published papers.

“make information about you (e.g., your name, institution), about the data and/or code (e.g., origin, version, associated files, and metadata), and about exactly how you would like to get credit, as clear as possible.”

It is astounding how many repositories on the GitHub have no contact info for the author!

Reward colleagues who share data and code¶

- GIVE THEM CREDIT in the way they ask you to.

- Credit is cheap, but a major currency in academia - give them credit.

- Give them praise, in person and in the community (i.e., when you give talks)

- Mention this work in letters for promotions and recommendtions

- Promote the work of colleagues whose data have really helped your science: invite them for talks, nominate them for awards.

- Get familiar with the DORA recommendations (https://

sfdora .org /read/) and promote them at your institution.

Be a booster for open science¶

- Foster these practices in your own groups. Allow students the time to learn new tools with the promise that they will be more efficient researchers later.

- Make sure students understand the effort that goes into developing open data and software and they also follow proper citation and attribution practices.

- Appreciate that doing all of this takes time and energy and be an advocate for your colleagues when they are up for performance appraisals, promotions, awards, that this effort is recognized.

- Get familiar with the DORA recommendations (https://

sfdora .org /read/) and promote them at your institution.

Progress will not happen by itself. The practices described here are increasingly incentivized by requirements from journals and funding agencies, but the time and skills required to actually do them are still not being valued.

At a local level, principal investigators (PIs) can have the most impact, requiring that the research their lab produces follow these recommendations. Even if a PI doesn’t have a background in computation, they can require that students show and share their code in lab meetings and with lab mates, those data are available and accessible to all in the lab, and that computational methods sections are comprehensive. PIs can also value the time it takes to do these things effectively and provide opportunities for training.

Many funding agencies now require data-management plans, education, and outreach activities. Just having a plan does not mean you have a good plan or that you will actually execute it. Be a good community citizen by setting an example for what good open science looks like. The true cost of implementing these plans includes training; it is unfair as well as counterproductive to insist that researchers do things without teaching them how. We believe it is now time for funders to invest in such training; we hope that our recommendations will help shape consensus on what “good enough” looks like and how to achieve it.

- Goodman, A., Pepe, A., Blocker, A. W., Borgman, C. L., Cranmer, K., Crosas, M., Di Stefano, R., Gil, Y., Groth, P., Hedstrom, M., Hogg, D. W., Kashyap, V., Mahabal, A., Siemiginowska, A., & Slavkovic, A. (2014). Ten Simple Rules for the Care and Feeding of Scientific Data. PLoS Computational Biology, 10(4), e1003542. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003542